This article is written by;

- Dr Per Arne Persson, LtCol (Ret), prev. Swedish National Defence College

- Prof (em) James M Nyce, Ball State University, Muncie, IN, USA

- Jan-Inge Svensson, Col (Ret), Folke Bernadotte Academy, Stockholm

Abstract

New types of conflicts and wars trigger development of new technologies, tools and methods. Clearly, technology can be bought and fielded to support the intelligence cycle but must fit the organizational and operational contexts. If not, intelligence methods and tools easily become a patchwork which requires much effort to make efficient. The common response in such a situation is “better” systems engineering. While ambiguity may facilitate negotiations, intelligence results in such conflicts can unfortunately be interpreted in more than one way, if they get any impact at all. In such cases, better systems engineering is no remedy.

Wars during the early 1990s challenged traditional military intelligence because they were not fought between nations or between the major powers’ pacts or alliances. Instead they involved coalitions and a variety of often seemingly irrational aggressors. During the First Gulf War (1990-91), massive efforts were made to develop and field automated collection (sensors, unmanned aerial vehicles, UAVs) and distribution of intelligence. HUMINT, when humans are sources, remained crucial. However, analysis became a bottleneck, later to be “remedied” with new visualization tools.

The paper presents some first-hand experiences from the multipolar and ambiguous wars in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia when a coalition of UN forces – also a patchwork – did not fight a war but was deployed in one. Previously, intelligence had hardly been recognized as part of any UN mission. Consequently, the intelligence resources were limited, constraining actions and responses. Yet the UN forces tried to, and often succeeded in discerning what was going on, struggling to enforce peace according to their mandate in close contact with belligerents. Traditional intelligence approaches were applied together with unorthodox ones and form a fresco over intelligence challenges and how these were dealt with. We will describe and discuss events, how experiences were used in Sweden, and then outline elements in development of the intelligence function. The lessons here are (1) that further evolution of intelligence should be a concern for all in military and civilian organizations, not only the few who form, field and lead intelligence units; and (2), that what is a “fact” is a matter of politics.

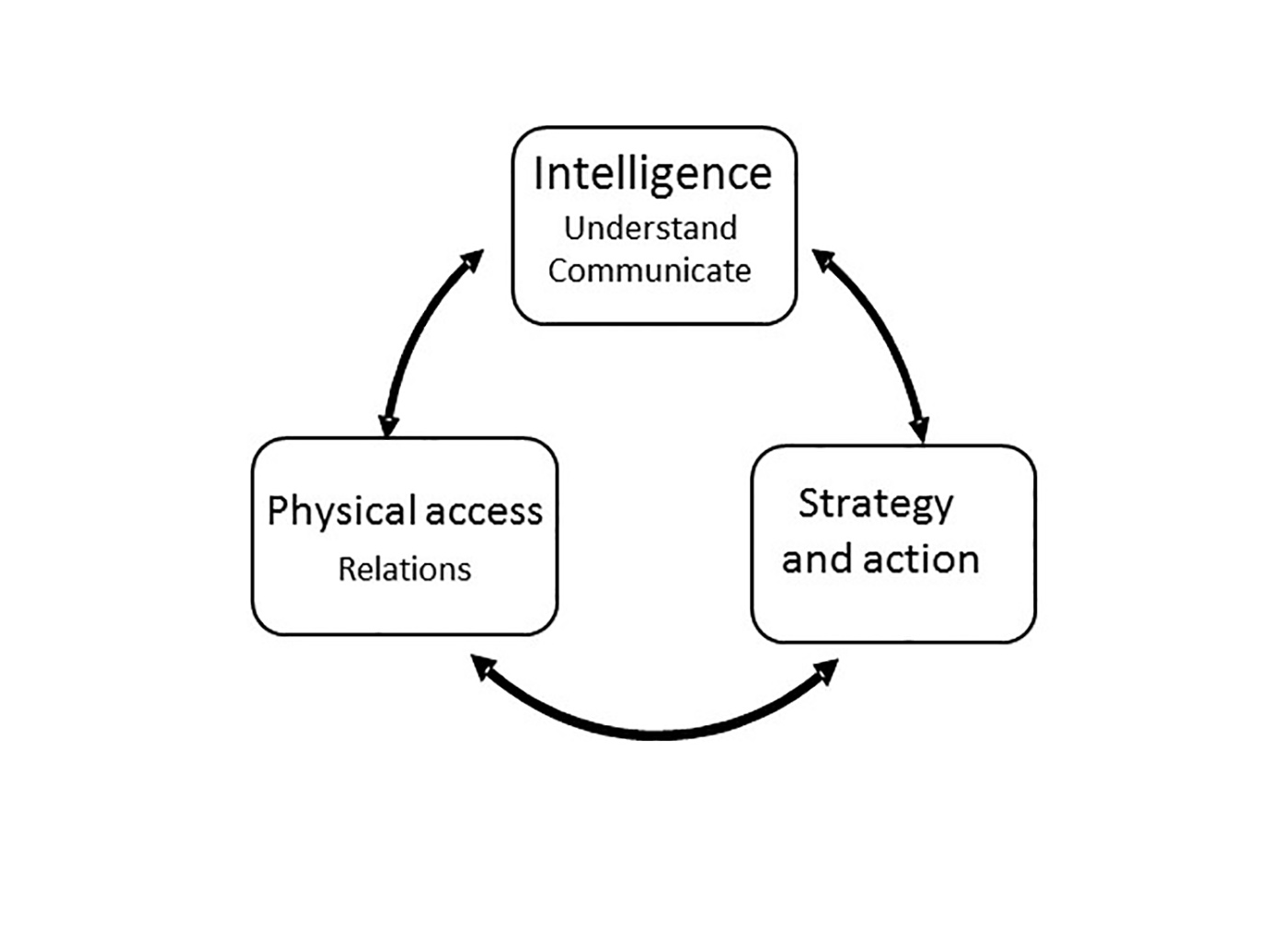

We have applied systems theory, using the term boundary zone – the borderland between an organization seen as an open and negotiable system, and its environment – as a key concept. Everyone in an organization in a mission area lives in this zone, sharing the responsibility to observe, report, and act for the survival of that organization. In the current state of intelligence studies as an academic field where insights about intelligence as a discipline are developed, including scientific methods for such studies, we claim that our work illustrates an approach where classical theories (sociology, systems theory, politics) are useful and should be paid attention to. Intelligence is far from a rational, technical enterprise.

We hope this perspective will inspire those in and outside of the intelligence community to work together to develop and extend this community’s professionalism and “reach”.

Content

Managing the Boundary Zone – a Swedish Perspective on Intelligence in the Balkan Wars. 1

About this paper and its links to the Operational Situation.

Operations in the Balkan Wars and Intelligence Challenges.

Introducing Area of Responsibility (AOR), Mandate and Empirical Field.

The First Nordbat 2 – trying to be Firm, Fair and Friendly.

Mission policy, deployment and operational context

The Second Nordbat 2: BA02 established relations in the area.

UNPROFOR HQ in 1995 – closing the gaps.

The conflict and the UN intelligence system up to 1995.

The situation in the UNPROFOR HQ..

Epilogue – further development of the UN intelligence.

Summarizing intelligence during the UNPROFOR/UNPF operations.

Developments in Sweden after 1995.

Interviews and personal communication.

Introduction and Theory

This paper focuses on the UNPROFOR/UNPF[2] operations 1993-1995 in the former Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (hereafter FRY) during the early 1990s Balkan Wars. The political and military situation more than new technologies affected intelligence, its methods and its results.

Intelligence was hardly recognized within the UN until the Balkan Wars and the Rwandan genocide (1994) demonstrated the need for such recognition. Furthermore, a UN-led operation with a coalition aiming at peace-enforcement – more demanding than traditional peace-keeping – was a new strategic and operational challenge. In his accounts of command experiences in Rwanda[3] (2000), General Dallaire even claims that peace support operations require a much broader range of skills than do conventional warfighting.

Using the term military information had hitherto been a way – rhetorically at least – to attempt to stay impartial in such conflicts (no friend-foe relationship between UN forces and those who were active in the wars) but turned out to be counterproductive. The dynamic and complex circumstances – politics, organization, environment, conflict – made intelligence, or rather surveillance, necessary but problematic. The UN forces did not fight a war but were deployed in one, with limited resources and many restrictions as regards actions and responses. It took years before the intelligence structure was more than a patchwork.

When the first military units were deployed (here represented by the Nordic battalions in Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereafter Bosnia)) the priority was to get access, freedom of movement, to understand and ideally control the situation on the ground. These efforts continued during 1994 and 1995, with the UNPROFOR/UNPF HQ trying to integrate a variety of resources and form a satisfactory intelligence structure.

Intelligence (“military information”) during these UN operations during the early 1990s, has been extensively described, discussed and criticized (Eriksson, Rekkedal and Strommen, 1996; Wiebes, 2002; de Jong, Platje and Steele, 2003). What more can possibly be said about the UNPROFOR/UNPF operation that sheds light on UN intelligence and maybe even on intelligence in a wider sense? The debate so far has addressed its legitimacy, fragmentation, unsatisfactory communication between tactical and strategic/political levels, and shortcomings as regards skills and equipment (ibid.). Another discussion concerns the operations of UN units and their efforts individually and together, how NATO nations in parallel deployed exclusive intelligence resources, and how parties from time to time changed loyalties as regards exchange and collaboration with the UN forces and between themselves.

Intelligence research has traditionally been theoretically weak (under-theorized), (Eriksson 2013) but has gained intellectual momentum during the last decades. Our empirical contribution is mainly a qualitative analysis of the experiences of some persons who participated in the operation, from actions during a three-year period when the war and the conflict slowly changed character. Our theoretical contribution is to use systems theory as a means to achieve a more holistic view on intelligence in general and specifically as regards UN intelligence in the Balkan Wars.

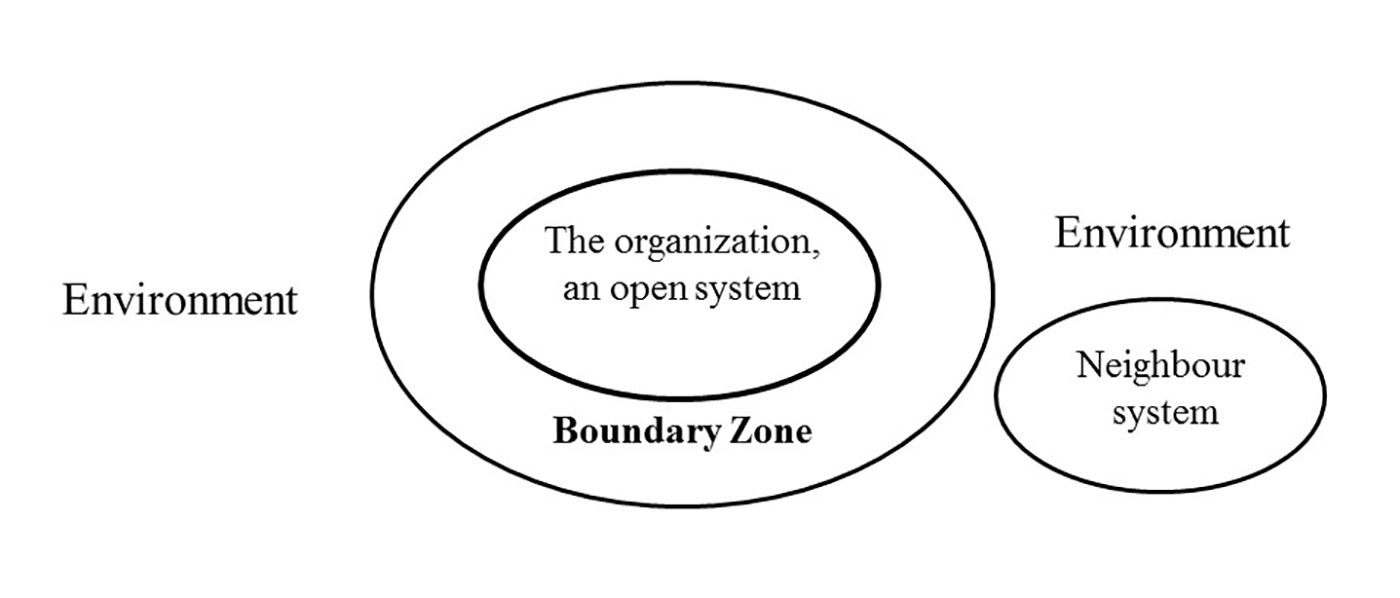

The essence of this perspective is to see an organization as an open system (Scott, 1998) surrounded by a boundary zone toward its environment (see figure 1). By definition, it is surrounded by other systems, some collaborating while others are opposing, maybe even openly hostile toward the system in focus (Stevens et. al, 1998).

Figure 1. An organization as an open system with a boundary zone towards its environment with another system – here a neutral one, no boundary zone, influences or relations inserted.

This type of system has a social and a technical component; it is a sociotechnical system. In system theoretical terms an open system exchanges material, information or energy across this boundary and has to take action in response to environmental changes, if it wants to maintain a steady state, by controlling this exchange (Flood and Carson, 1993). The abstract term “Information” spans any kind of communication, conscious or not, including what is visible or detectable by someone outside a certain system. Also, the border between matter and energy is blurred when we refer to its substance.

Moreover, a system’s boundary toward its environment cannot be defined once and forever; it is often arbitrary (Emery, 1969). Whether an external entity or, in system terms, a potential system component (in battle also an adversary) can be controlled or not indicates if it belongs to the system or is in its environment. Weak “influence” of this component indicates that it is in the environment. Therefore, instead of using boundary, we prefer boundary zone. Components can move or be brought into the boundary zone and even into the system, and they can leave.

Early development of systems theory underlined the need for boundary management (Emery and Trist, 1969; Emery, 1969), to understand and control the exchange across the boundary between an organization and its environment, its context (see figure 1). “Exchange” can mean communication, combat or firing. The technological component can, for example, extend or limit what can be done and create demands on the internal organization of an enterprise. “Softer” resources, pre-understanding and language, may be even more fundamental for successful boundary management. These allow the change of perspectives on a situation whereby more of the boundary zone and the environment can be inspected and influenced. For example, our informants meant that their Cold War mind set was useless in Bosnia. They had to come up with another perspective on the conflict in order to understand what went on – and expand their territory.

We use this basic model and expand it somewhat to illustrate our arguments about the intelligence function. In order to explore the environment, relations have to be established with it, or more specifically, with social actors in it, including organizations. By succeeding with this, the organization as a system can understand and control more of its close environment. Deception is a special kind of control, relying on communication directed at some actor in the environment (in another system). Unless discovered it has little value. Within UNPROFOR/UNPF negotiations and socializing (coffee and a slivo drink often better than use of force) were instrumental to gain freedom of movement, but had to be supported by intelligence: Who were the persons involved, their history, objectives, and relations?

To use the term “boundary zone” has three facets, two practical and one theoretical. The first concerns “practical-political” matters, such as getting physical access, freedom of movement, transport to and inside an operational area. Relation-building is one concern, another is to establish a platform for communication: Who talks to whom and how? And still more important: Who is allowed to talk to whom – often a matter of rank, power position, and thereby close to politics. Communication protocols may be required.

The second, which the model helps with, relates to the practical, technical and cognitive aspects of understanding a situation, phenomena and events, and the communication about what is ongoing internally and externally. In short: this is what intelligence work is about – eventually production and then (often selective and fine-tuned) dissemination of results – and involves social and cognitive issues. Once these two facets have been covered, informed action can be initiated.

The third is about the theoretical understanding of intelligence work from the perspective of seeing an organization as an open system. This concerns issues such as goals, relations and dependencies, the foundation for institutionalization, which can guide education in general as well as organizing, planning and deployment for intelligence operations.

About this paper and its links to the Operational Situation

The publication of the personal accounts of the first Swedish battalion commander in Bosnia,[4] COL Henricsson (Henricsson, 2013), inspired us to a closer look at intelligence in this war.

The reason was that we, the authors, have worked with the Balkan Wars and intelligence service in various ways and now, in addition, saw an opportunity to use the open systems perspective to illustrating how the intelligence function – although it did not formally exist in this UN context – was a concern for each and every one in in the mission. Persson studied the experiences of the first two Nordic battalions in Bosnia (BA01 and BA02) that were deployed in 1993 and 1994 (Persson, 1997). In order to update original 1994-95 data, Persson has interviewed (2015) officers who served with the first battalion, its commanding officer, one intelligence officer and its signal officer, and has used its after mission report (1994).

Svensson served as Chief Information Officer (G2) within UNPROFOR/UNPF (Zagreb) in 1995. As such he was responsible for intelligence in ex-Yugoslavia, specifically in Bosnia, Croatia and Macedonia (FYROM[5]) (see Svensson in Isberg et al., 2014; Svensson in de Jong, Platje and Steele, 2003). Nyce has worked with Persson and Svensson at the Swedish National Defence College (NDC) from 2006 up to 2011 in a research project aimed at the development of the Swedish military intelligence. Previous studies on UN intelligence that have been consulted are Eriksson et al. (1996), Eriksson (1997) and Wiebes (2002).

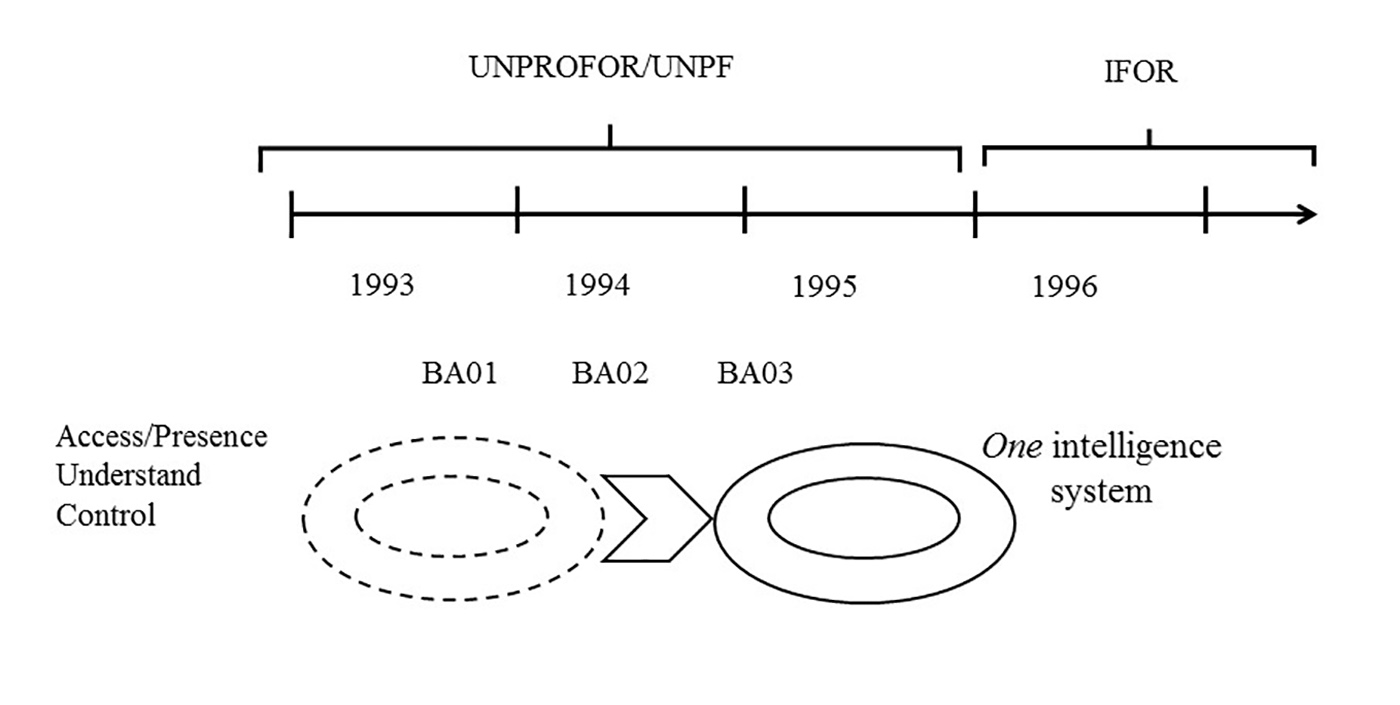

Here we describe the build-up of the intelligence system from the early UNPROFOR/UNPF period during 1993 and 1994 when the Nordic UN ground forces (BA01, 02 and 03) struggled to get access, understand and manage the situation. The whole force structure was turned over from year to year as in most UN missions. Eventually (1995) the system was area-wide, efficient, trustworthy, and could make, at times, accurate predictions. In all, we see the UNPROFOR/UNPF intelligence system as the result of an ongoing dynamically shifting bottom-up development that had to overcome many obstacles, a process that reflects the relations between this system and its environment (Figure 2). Access and acceptance had to be achieved, before understanding and some degree of control could be established.

Figure 2. The UNPROFOR/UNPF intelligence system, from patchwork to unity.

A “Swedish perspective” means three things:

- An understanding of how the Swedish (Nordic) units handled the situation, understood and organized their intelligence work during 1993 and 1994. This presentation includes methods and technologies.

- A review of experiences that were brought back to Sweden and how they were implemented in the decade after the Balkan War, in the military and at the Folke Bernadotte Academy.

- The use of systems theory as a framework to discuss and interpret intelligence activities, a model that was developed at the NDC. This approach is a logical extension of the first two, and makes it possible to see the UNPROFOR/UNPF phase as a whole.

The paper is not intended to be a scientific examination of the intelligence work within UNPROFOR/UNPF, its process, progress, methods or results. Neither do we desire to evaluate the intelligence function or judge whether, or how, the units or those who evaluated them reached (“true”) conclusions.

Instead we have looked at intelligence work, especially at the micro level, how it was done and what it achieved, and how it was adapted according to the circumstances, especially methods and how certain technologies were used. This paper will look at cases that exemplify how the forces on the ground, especially the Swedish, perceived their environment, the type of events they were confronted by and how intelligence and the role it played changed over the course of the operation.

We will focus on two kinds of experiences. One is how the first two Bosnia battalions handled their intelligence issues and operations. The other “window” to the operation is when Svensson in 1995 was appointed to the position as Chief Information Officer (G2) in the UNPROFOR HQ and how he acted in order to make the system function satisfactory (Svensson, 2014). During his service, for example, the first efficient register for storing reports was fielded, developed by G2 from a commercial off-the-shelf application. This register was but one of the steps to transform a patchwork into a more solid intelligence system. Experiences from the conflict and the operations affected the evolution of Swedish intelligence and we will summarize this process.

Thus, our contribution is an experience- and a theory-based view from a Swedish perspective on intelligence, built from previous research (Persson, 1997) and personal experiences (Svensson, 2014; Henricsson, 2013).

Operations in the Balkan Wars and Intelligence Challenges

Introducing Area of Responsibility (AOR), Mandate and

Empirical Field

After World War II Yugoslavia consisted of six republics and two autonomous regions, each one having its own ethnic-religious-political profile. The declaration of Croatia and Slovenia in May 1991[6] to be independent from the Serbian-dominated central government in Belgrade started the breakup of Yugoslavia. The ever-changing political landscape over centuries had led to (and reinforced) distrust between different national and ethnical subgroups.

Actually, it is far from enough to start an analysis of the situation in the Balkans with World War II. By the end of the 19th century and up to the First World War – the fatal shot in Sarajevo in July 1914 and the nationalistic sentiments behind it – the combination of local and regional political ambitions accompanying the formation of modern Turkey, and the involvement of the dominating European states (See Lieven, 2015[7]) had created an explosive cocktail. Its ingredients and the manner in which they were mixed – abrupt movements – were well tested in the late 1980s.

The first Nordic battalion to be deployed in Bosnia, BA01, arrived in its area of responsibility (AOR) around Tuzla in North Eastern Bosnia[8] in late September 1993. The UNPROFOR mission was in a critical phase and only days remained of the mandate. Eventually, it was extended six months to the end of March 1994 (when again uncertainty grew about its continuation[9]). The battalion was deployed in a boundary zone in more than one aspect – the mandate, relative to the three warring factions, and theoretically: Once in Bosnia, the whole environment was new; there was a boundary zone from every aspect.

Contingents had national mandates, meaning that their participation under UN command was constrained in more than one way. The length of the deployment was six months. Units from smaller nations which were not NATO members were “victims” of the agendas played among the major powers (mainly UK, USA, France, Russia) inside and outside the UN. The mission was a patchwork, organizationally and technically as can be seen in the UN map 3684 Rev. 2 by February 1993 (Figure 3 is a map extract).

Figure 3. Extract from UN map February 1993, with Bosnia and part of Kroatia. Red symbols mark BHC. Photo by Per Arne Persson, February 2015.

The mandate was basically peace-keeping (UN Chapter VI) but the Rules of Engagement (ROE) allowed the use of force not only for self-defense, which made the mandate more peace enforcement[10]. In spite of this, the units were not to take the initiative to use weapons/force. Their objectives were to provide military assistance to the UNHCR and other approved humanitarian organizations in Bosnia, and to open and coordinate all activities at the Tuzla airport. Movements into Bosnia and across front lines in order to separate belligerents had to be agreed upon and deployment done without combat/use of force. As regards military units in the area, the battalion was deployed among the AFBiH[11] units (which previously had held the airport), with Bosnian Serb forces holding terrain on three sides (north, west and east) and the Bosnian Croat HVO[12] on the fourth.

Maybe the (political[13]) choice of area for Nordbat 2 around the city of Tuzla was the result of insufficient intelligence – the area was estimated to be rather calm (interview with a former Information/Intelligence Officer (IO) February 2015). It was not. The next section will describe actions and experiences of the two first battalions (1993-94) and in the intelligence section (G2) in the UNPROFOR/UNPF HQ in 1995.

The First Nordbat 2: Trying to be Firm, Fair and Friendly

The bulk of the BA01 battalion was three Swedish mechanized infantry companies with APCs (on tracks and wheels[14]), a Danish tank company (10 Leopard 1 tanks), 9 antitank missile teams, and combat support units (HQ/supply company). Norway provided a field hospital and a helicopter squadron (4 helicopters). There were no dedicated intelligence units. Sights for antitank missiles, on the tanks, and night vision goggles made night observation possible. In the area was also a Jordanian (UN) artillery localization radar company which could confirm who fired at whom when the parties accused each other (COS June 1994).

The mission had several subtasks (a simple area sketch by the former Information Officer February 2015, see figure 4). An excerpt from UNPF BHC 1993-12-03 Fragmentary Order (reproduced in the BA01 after mission report) says:

“Provide military assistance to UNHCR and approved organisations and agencies involved in humanitarian activities and repair of utilities in BH.

Establish conditions favorable to

* The evacuation of the wounded

* The protection and care of the people

* The improvement of the living condition of the people

* A cessation of hostilities

Maintain the status of the “Safe” areas of Sarajevo, Tuzla, Gorazde, Bihac, Srebrenica and Zepa…”

Figure 4. Sketch of the BA01 area, illustrating how the battalion was deployed among BSA, HVO and BiH forces. Vareš and Stupni Do at the bottom. Photo by Per Arne Persson, February 2015.

The continued development showed that the meaning of “Safe area” and “conditions favourable to….” was far from clear.

Our BA 01 data consist of

- after-action interviews in 1994 with the battalion Commanding Officer (CO), the Chief of Staff (COS), the Operations Officer (OO), the Signal Officer (SO) and a company commander,

- the after mission report together with some other contemporary (1994) documents.

- two follow-up interviews February 2015 with one of the Intelligence/Information Officers (IO) and the former Signal Officer (SO).

- Email communication with former IO and conversation with former battalion commander in April 2015.

We will describe intelligence in the field by illustrating surveillance and cooperation, assessment and reporting, before concluding on some topics. Doing this, we cover mainly collection, one of the phases in the intelligence cycle, the standard model for intelligence work.

Mission Policy, deployment and operational context

In this boundary zone, BA01 had to interact with opponents, create or enforce social relations with them, so as to communicate with and influence them– maybe even “manage” and control them. The motto “Firm, fair and friendly” guided their practice. As it turned out, FIRM had to be demonstrated repeatedly, in order to make way for humanitarian support. When the force arrived, fighting occurred along three established fronts and between the three parties (there were no “good guys and bad guys”), before the Croats and the Bosnian Muslims agreed on a truce. In spite of this, local battles and weapon duels occurred again and again. Still, pre-war relations across the fronts were found to be the backbone for black market trade and smuggling.

Movements and supply convoys from Pančevo in Serbia (to where the battalion arrived after its cross-Europe transport) into the AOR were strictly controlled at the border in Zvornik. There was a border bridge over the river Drina, in control of the Bosnian Serbs (“The King of the Bridge”). After the arrival, it was clear to the battalion that there was no peace to support. Periodically, intense fighting occurred all over the area and in all directions. During October and November, convoys could only sporadically cross the border, and two companies (mechanized infantry, tank) had to stay in Pančevo. Eventually, in January and February 1994, these could enter into the AOR after a transport back to Vienna, then via Italy on a ferry to Split (Memo JHQ 1995-12-21; Henricsson, 2013).

The Bosnian Serb leadership also opposed a UN intervention at that time (Eriksson et al., 1996). It seemed as if delays at the border were orchestrated because the UN made the situation in Bosnia better, specifically after the arrival of BA01. Its reports meant an indirect support for the other side. In fact, all roads were cut off during a few weeks in November 1993. About the same time General Mladic[15] wrote to the COS in the UN Bosnia-Herzegovina Command (BHC), complaining over the strength of BA01: it seemed to him as if it was organized for war rather than for peace-keeping. The more the battalion achieved, the more troubles BSA had arguing for their version of the situation (Henricsson, 2013). This was a war without rules where looting provided both pay and incitement (after mission seminar, April 1994).

Since the battalion’s arrival in the area and when companies had started to deploy in their areas in the AOR, its personnel were engaged in liaison and reconnaissance, visiting local BSA, HVO and AFBiH units, negotiating over freedom of movement and access to vital terrain – a precondition for its mission. Through negotiation, deception, surprise movements (also at night), and playing out the opposing parts against each other, the battalion could establish observation posts (OPs) and get access to roads for transport. But access was not always given. The armoured vehicles (APCs, 6-wheeled SISUs, tanks) proved valuable when the units frequently experienced artillery fire. Occasionally, antitank missiles were used, wounding BA01 soldiers and damaging their vehicles.

How then did the battalion and its intelligence function operate in this context? The intelligence section was manned with a Chief Intelligence Officer (or rather Military Information Officer, abbr. MIO), two Intelligence Officers (IO, who alternated as Duty Officers, DO[16]), some assistants and interpreters – very few, considering the amount of work. Here we consider some of their activities and illustrate how this battalion, which entered into the area with a “Cold War tactical mind set,” over time accomplished their mission, and how intelligence contributed.

Our qualitative analysis starts with events and actions in the field. In order to illustrate intelligence methods, tools and practice we use the intelligence cycle, the most common standard model of the intelligence process[17] as a reference, but pointing at its shortcomings or rather bias: The term collection, its second phase (see footnote), gives the impression that this is a straightforward activity. In this conflict, it was not. Instead we have “clustered” events and actions which generated insight under Cooperation and surveillance and brought together Assessment and reporting, because these activities are closely connected – assessment and reporting are tailored depending on the context and the receiver.

But first we illustrate, as a background and mainly through the eyes of the CO (COL Henricsson), an early experience and a worst case start for the first units that arrived in the AOR: the massacre in Stupni Do, a village with a mainly Muslim population near the town of Vareš, in late October 1993.

The Stupni Do events

One BA01 company commander reported (21 October) some fighting in the village where he was located – Kopjari 10 kms west of Vareš – between a Bosnian HVO brigade, the so-called Bobovac brigade[18], and the 3. Bosnian Corps. Two days later in a town about 25 kms south of Vareš, a Bosnian Operational Group commander informed Henricsson that an AFBiH attack was under way, aimed at capturing Vareš. The reason this officer gave was that soldiers from the Bobovac brigade in Vareš had attacked and burned down the nearby village Stupni Do. The meeting with this commander followed a failed first attempt by the BA01 CO to reach Vareš with a small team in a convoy: Manned roadblocks and fighting further north were too much, too risky. However, when hearing about this attack, Henricsson decided to return towards Vareš and find out what went on. The place was in his AOR, and he made an agreement with the Bosnian commander to return north: Both wanted to know what had happened.

Later the same evening, Henricsson advanced with only an armoured SISU vehicle along the valley towards Vareš while fighting occurred on the hills on each side of the road. He saw the night skies illuminated by fires from behind a ridge separating him from Stupni Do. But he could not reach the village; he only reached Vareš, where he met his company commander who two days earlier had reported about combat. Beginning this first evening, they tried to understand what happened behind mine fields, hostile local military and militia units, and repeatedly tried to negotiate access. After three days (26 October), in spite of efforts from units of the Bobovac brigade to conceal what happened (later confirmed), units from a mechanized company finally bypassed, removed or had tank mines cleared by the Bobovac units themselves, could enter into Stupni Do, and eventually discovered the remnants of a massacre.

The first BA01 units arrived immediately after a team from the BBC (Figure 5) which, for some reason, had been allowed to get through and dared to stay there, and could show the arrival of the Nordbat units to the world.

Figure 5. Col Henricsson walks into Stupni Do in the afternoon on 26 October together with the tv team in front of the SISU vehicle. Photo Magnus Ernström, vehicle gunner[19].

Numerous signs of a massacre were discovered: mutilated dead bodies, in all fifteen, some of which also were booby-trapped. The same afternoon Henricsson reported back for support in order to do forensic investigation.

After some days, when reading battalion reports about the events which had been sent to Sweden, Henricsson got very upset. They did not describe what the units had witnessed and done. He was told that reports sent on were just a summary of the Vareš reports. They were not incorrect, but they gave no sense of the reality of the events in the village, no fear, darkness, or odours from fires and dead bodies. He concludes that this should be captured in the reports sent upwards – those who read them in another and safe environment do not understand half of their content or their implications (Henricsson, 2013).

This whole situation illustrates the everyday reality for the battalion. The fighting factions could erupt in combat with each other as well as with the UN force, a shortage of equipment due to convoy delays, constrained freedom of movement, and extended lines of communication. In addition, the environment was harsh. Mountainous terrain and later on winter conditions made it even harder. Independently of the UN policy as regards intelligence, there were multiple threats to the survival of the battalion. Atrocities were unbelievable – how to make them intelligible to the world?

In short, everything became intelligence – improvisation made the difference.

Recalling the concept of boundary management, the battalion had to bridge not only the social, mental and physical boundaries to the warring factions, but also to the UN and national authorities. Now we illustrate some aspects of intelligence work.

Cooperation and Surveillance

The battalion had to establish and maintain relations with all parties, military (UN forces and local alike) as well as civilian, belonging to UNPROFOR, UNHCR, international NGOs, or locals. Given the basic acceptance of the UNPROFOR mission, the mandate, and according to the very late fact finding reconnaissance during the summer – which limited its value – when the force arrived in the area in the fall and winter of 1993, it negotiated the positions of camps for its subunits with local authorities and forces. The 2. AFBiH Corps handed over their area to the battalion. However, political frictions affected what was possible, and the battalion was not prepared to handle the later difficulties and delays regarding the transport from Pančevo in Serbia into Bosnia. Thus, meetings and contacts could be informal and friendly, formal and correct or outright hostile encounters.

The local power structure was difficult to map and navigate in. It was important to learn who the right persons were, to visit them, to gain respect and credibility. For example, a brigade commander was not always the one who was in command. Instead, a political officer could be the true power holder (Henricsson, 2013).

The LO found that face-to-face contacts were preferred when encountering locals, as well as representatives for international organizations – an individual had to appear trustworthy before a breakthrough in the relations (1994 interview). Trust in these environments is never stable, always subject to negotiation and re-negotiation. Pre-war managerial and administrative practices in society meant centralization and little transparency. Therefore, when facilities were closed down, it could be very time-consuming to find out basic facts. One example is a chlorine industry in Tuzla: it took months before basic facts about its production were revealed (1994 interview with SO).

Thus, the BA01 Operations Officer, for example, found it wise to spend some time on dinners and cocktail parties:

“At the end of the day one solves certain issues and gets to know the other better over…..a steak and a glass of red wine than over a situation map.” (interview 1994, translation by first author)

The feelings towards NGOs and similar international partners were mixed. Some were sceptical of the military, but “I used to say that we are actually here to help these idiots and therefore we do it. We don’t need to love them but if they hadn’t been here neither had we” (Ibid.).

From early on, the BA01 leadership visited local forces and civilian authorities for negotiations, signing contracts on resources, or offering support. The battalion CO spent much time in the AOR and was helped by his rank – a colonel can outrank and confront many a gate-keeper. On the other hand, he had to inform his colleagues about his contacts and discoveries, about the warring factions, other parties and about the terrain. At the after mission seminar in April 1994, the CO meant that when all relations are at their best the deployment ends. In spite of this, the OO thought that it was quite unproblematic to transfer the area when BA02, the successor, arrived in the spring of 1994. But their Bosnian parties probably found it frustrating – what relations were worthwhile to invest in?

Also, the company commanders negotiated. One of them described how he and his team – interpreter, staff sergeant and himself – wrote some of the protocols from meetings collaboratively (1994 interview). Compared to the subunits in the battalion who were encouraged to take initiative, most often local counterparts were not used to or did not dare to.

In order to get access and then freedom of movement, the capacity of roads and terrain were of crucial importance. The combination of a modern military force and its heavy and large vehicles in an area with mountains, narrow and old roads, streams and weather conditions that varied considerably over a year as well as in each season depending on the place made surveillance, “terrain intelligence”, a vital function.

In general, the roads were in bad shape. Tank mine fields canalized forces to the roads. Those which were paved, metalled, or used by civilian traffic were considered fairly safe (former IO, email communication 2015-04-29). Mountain roads were narrow and often crammed with traffic but became the only alternative because of the fighting and widespread destruction. The armoured vehicles, especially, were broad and heavy which meant that bridges had to be carefully examined before passing them. Narrow road tunnels further complicated movements, especially for trucks loaded with containers. The former Signals Officer (SO) illustrated (February 2015) how in some tunnels a layer of gravel had to be put on the carriageway which elevated vehicles to a higher level where tunnels occasionally were wider (Figure 6). Trucks had to be unloaded and technically modified in order to pass tunnels and overcome provisory roads respectively. Drivers’ skills, achieved in the Nordic terrain and climate (but without a war), were challenged but remained good capital.

Figure 6. Former SO shows how extra gravel in tunnels could allow for wider vehicles to drive through when they passed on a higher level. Photo by Per Arne Persson, February 2015.

The winter weather made any transport a matter of hours and days, with fighting and roadblocks – often complete with tank mines (occasionally booby trapped) – being additional obstacles. Local HVO forces occasionally escorted Nordbat units. Judging from Henricsson’s (2013) accounts, the construction of the mines was well known, which made it possible to handle and clear them.

Map supply was a bottleneck. When arriving into the AOR, there were only a few (1:50000) in the battalion HQ, at the companies, and enough to convoy leaders. They were not personal but had to be handed over to those who needed them. One of the few AOR maps (1:50000) was sent to the Swedish Prime Minister after a special request – he closely monitored events in his office (former IO interviews February 2015; email communication 2015-04-30). UNPROFOR delivered maps, but they were old, although completed with road networks marked with capacities. Altitude curves were missing or unreliable; the resolution was low. Later, maps were also printed in Sweden. Yugoslav maps were excellent but few, but classified as secret. Occasionally, some were captured or achieved after pleading for them (Henricsson, conversation 2015-04-29).

Contraband items were cameras, video cameras, and large radios. Regulations about the use of cameras were strict. They had to be carried in pockets, not openly. The Serbs especially were allergic to cameras. Henricsson (2013) mentions one event when a convoy was stopped in a checkpoint at Zvornik for six hours because two drivers had their cameras visible in their vehicles. Everts (2000) recalls how negotiation between the Serbs and U.N. had led to regulations concerning rotations in and out of the Srebrenica enclave.

The main surveillance resources were fixed Observation Posts (OPs) complemented by mobile ones in the form of APCs whose positions changed from day to day. OPs were linked to the supply roads and the traffic, and most often positioned on hilltops. Artillery positions could be calculated by triangulation when more than one OP listened and measured distances and directions. Daily reports with statistics were sent to the battalion HQ, but all the dynamics were not caught. It soon became evident that convoys were the most valuable surveillance source – they crisscrossed the area and the region. They were often fired upon with artillery, or maybe the fire was directed at outposts and road blocks from either warring faction. It was not always possible to define who fired when convoys just happened to be close. This occurred sometimes even when permission to pass had been negotiated. Escort commanders, truck drivers and convoy leaders who became familiar with the environment were interviewed in the HQ, and described their travel observations and impressions.

“We met them in evenings, platoon commanders, escort personnel and drivers who were filled to their brim with the day’s events and with high pulse, tried to take down what they said in front of the map in the operations section.” (IO February 2015, translation by first author)

The lack of proper equipment had to be compensated for by improvisation. The former IO described (February 2015) how, when Bosnian Croat forces (HVO) cut off a valley already surrounded on three sides by BSA forces (“the Maglaj pocket”) and started to bombard the fenced in BiH force, reports reached the battalion about civilian casualties and firings. Their most western OP could hear the distant artillery fire, but it was not possible to verify the events. Eventually, radio traffic was intercepted, senders were technically located, and interpreters could identify how the HVO fired intensely at Maglaj outposts; explosions could be heard “behind” conversations from someone sitting in a cellar.

NATO organized its own intelligence operations in the area. Military personnel equipped like UNMOs[20] but armed appeared in the AOR, even driving white vehicles – what did they do? They could compromise UNPROFOR. Some teams were believed to come from the British SAS and got a nickname: GUNMOs (former SO, February 2015). But reporting to London, they were, actually, a precondition for the UN operation, the Intelligence DO meant. There is an understatement here: exchange of intelligence (military information) between deployed national contingents was constrained but nations, NATO members or not (e. g. Sweden), informed their contingents about the situation. “London” could then inform the less-equipped UNPROFOR units (see details in his communication in the UNPROFOR/UNPF section below).

The Intelligence DO described how he tried to create a tool which would facilitate reporting – a reference map – when a new convoy road (Marion Road) between Tuzla and Vareš had been opened in the west near the village of Ribnica, close to BSA positions. He photographed the terrain when he was moving along the road in an APC, trying to capture places where BSA positions were discovered or could be deployed. After the film had been sent to and developed in Sweden and prints sent back, he intended to have them pinned next to a map on the wall as a reference chart with each photo related to a specific position. But once the road was used, the BSA never intervened and there was no need for this map. Figure 7 shows part of a contact print from one of these Marion Road films.

Figure 7. Part of a film contact print sheet with pictures taken by former Intelligence DO along Marion Road. Photo by Per Arne Persson, February 2015.

Assessment and Reporting

During the training period in Sweden before deployment, the intelligence DOs produced a traditional handbook with facts about the military forces in the AOR, with pictures of equipment and the names of force commanders. But the handbook was put on a shelf and rarely used. The actual military activities were more important than structures and names.

The S2 (Intelligence) section tried to understand what happened: Why was there fighting in some places and not in others? It became evident that assessment of incoming reports from only military viewpoints was insufficient. Also economic and political aspects had to be applied, as well as social and historical perspectives.

The former intelligence DO explained (February 2015) how they often were informed by the 2. AFBiH Corps, often correct even if dramatized, sometimes false – nevertheless it was possible to discern event patterns. In Bosnia, trust was always an issue – and a combination of deception, truth and flattery was always a contact strategy.

There was no specific computer tool for support of intelligence work, but indicators for support of assessment were developed. For example, indicators that something was about to happen were:

- Presence of extremist bands;

- Enforced evacuation of the population and refugees;

- One flag is hauled when two parties normally show both flags together.

- Peace negotiations: simultaneous firing could be used as a lever for result.

Indicators considered useless were all kinds of assertions or claims, as well as circumscribed freedom of movement (After mission report 1994-04-25).

Mass media were appreciated sources. The LO meant (1994) that the BBC was the most objective one and faster than the chain of command. Local media content, however, was biased and had to be filtered from propaganda. Media analysis nevertheless gave the battalion knowledge about different parties’ understanding, which could change over time[21].

They were, said the intelligence DO (2015), informed by the population that Bosnian Serbs and Bosniaks exchanged something during nights and so came to realize that it might be wiser to count fuel-loaded trucks than tanks. The BSA was rich on weapons but short on diesel, while their AFBiH opponents who got UN supplies had few weapons but a fuel and food surplus. Since the supply system “leaked”, the military had got hold of some. A kind of surplus subsequently was built up and traded for munitions and weapons during local cease-fire agreements. Since business relations were built on pre-war friendship, and exchange was beneficial for both parties, local cease fire agreements were made whereupon trading could start. It is these kinds of social and military ambiguities that challenged intelligence collection and analysis.

The battalion DOs routinely visited and worked at OPs, which meant that they learned about the local conditions, made friends with soldiers and platoon commanders, and, thus, could easier understand and interpret reports. The (former) intelligence DO also described how he accompanied convoys. In case of questions, they could easily call those who reported, whom they often knew, and clarify facts. Similarly, battalion DOs visited the BHC command that was located in Kiseljak.

The (former) SO believed (1994, 2015) that the battalion’s VHF radio communication could be intercepted. VHF radio traffic was overheard and could mutually inform BA01 and BSA/AFBiH about their military activities. It was beneficial for the UN force to know about the BSA intentions before negotiations (after mission seminar, 1994). Due to the mountainous terrain, relay transmitters were necessary and required protection, an arrangement which could make reporting confusing because a message could travel via a number of mediators. The battalion asked for, but did not get, new equipment from Sweden for encrypted VHF radio communication.

Companies sent in daily situation reports which were compiled, sent further to BHC in Kiseljak the same evening and to Sweden the next morning. Report forms and templates for the domestic reports were developed on location while the reports to BHC followed UN norms. At one of the companies, a staff sergeant initially developed a computer-supported reporting system and could produce and store reports for future retrieval. Automated, standardized formats and reports were considered beneficial, but speech was considered necessary when it was not possible to categorize or assess what happened according to predefined forms or concepts. The risk of monitoring the radio communication was neglected – understanding was a priority (Company CO, June 1994). Their standard computerized reporting system, built on short wave (SW) radio, was more secure – no voice communication. Satellite telephones were used both between battalion HQ and companies in the field and for communication in and out of the AOR, but remained a bottleneck.

Sweden was not a NATO member, which hampered the Swedes. Their Norwegian and Danish colleagues came from NATO nations and could get access to NATO area intelligence. It was, therefore, tedious for Swedes to get fresh intelligence and involved any number of workarounds. One exception was when they got a database directly from a US American source, containing data about villages’ ethnicity and religion. (“We should have had that from the beginning!” interview with SO, 1994). S2 then created an area map where villages were marked with colour according to their ethnicity and religion – a church or a mosque? Soon a mosaic emerged. When a certain village had been visited, the visitor was interviewed about the place – was there still a minaret or had it been destroyed, i.e. had the village been captured by opponents? Over time, markers were changed and illustrated how the conflict evolved. Later, when this (former) IO visited the fourth battalion (BA04), he found the map cleaned from the markers – after two years and three battalions this indicator might have become irrelevant (Intelligence DO, February 2015).

When reports reached the intelligence section (S2) about artillery fire, a team sometimes went to the point of impact in order to document and then report. The CIO was an army artillery officer and could analyse the traces of blasts and judge the type of weapon and from where a shell had come.

“It was sort of macabre when the team knocked on the door to a cellar where people were hiding: we cannot help you but would like to analyze the crater from the explosion” (IO February 2015, translation by first author)

Table 1 shows one example from a close firing summary, a confirmed (“Yes”) BiH mortar firing (mor rds) leading to a protest, close to a convoy in mid-December 1993 (CL= Confrontation line). We see the assessment in the right column:

Table 1. Extract from firing report December 1993

| 931214 | Memici

CQ 353210 |

BiH | 2 mor rds fired from CQ 333219 when Nordbat 2 convoy was passing. | By BiH | Protest to BiH 2nd corps. | Yes | BiH used the opportunity when Nordbat 2 was about to cross the CL. |

After another close firing when reconnoitring for an OP on a hilltop, Henricsson was certain that AFBiH fired, decided not to leave “his” hilltop – just to make an example – and writes:

“….actually they do not want us too close, at the same time they are dependent on the good will from the UN and want to demonstrate considerable acceptance to the UN. Then they scare us away and blame the Serbs. Rather cunning but the next time we will be better and position listening stations on other locations in order to measure and calculate where the guns are.” (Henricsson, 2013, p. 87, translation by first author).

The former intelligence DO described another example of analysis. Units had been fired at with wire-guided antitank Sagger missiles in February 1994. Two APCs were hit and five soldiers wounded. The metallic jet projectile produced by the HEAT[22] warheads penetrated the armour but passed between the soldiers, but luckily enough did not reach the ammunition. All survived with minor wounds. Afterwards, the missile’s control wire (the shooter uses a joystick to guide the missile to its target and instructions are passed via this wire to the missile) was found. It was possible to estimate from where and by whom it had been fired because the full length of the wire was known. In all, 137 close fire incidents were recorded (JHQ memo 1995-12-21).

Some initial assessment mistakes occurred. Certain “minor” incidents were not “minor” once they were thoroughly investigated – different opinions co-existed about reports. Now and then, frictions grew because of the compression of events (due to the communication system) in the reports that left the battalion (Cp. Stupni Do reports above). One company commander described how he sometimes could not recognize what had happened to his company when he read the report that left the battalion and complained: “Why didn’t S2 (intelligence) ask for confirmation before sending upwards?” (1994 interview)

Weekly and monthly reports to Sweden complemented the morning reports. The battalion COS found this system adequate: dailies and weeklies described what had happened from its perspective while the monthly reports were future-oriented (1994 interview). Behind the desk in the JHQ in Stockholm was an officer who understood the situation, who could call after a certain report: Is this really correct? The answer could be: It’s even worse. The battalion CO started to use CAPITAL LETTERS when he tried to communicate extraordinary events, but these were not powerful enough to describe what had happened.

After the first three months the conflict was defined as the struggle of the old nomenclature for defence of their wealth, power and positions, a fight with the help of extremists and war profiteers without conscience. To categorize the war as ethnic and religious only made it easier to handle politically. Locally, frequent short-term contacts occurred between the warring factions, something that should be encouraged – it could lead to peace. The BHC was criticized. Repeatedly, its personnel seemed to live in a world of negotiations, was naïve, and did not understand the situation outside Kiseljak (Henricsson, 2013).

Concluding about BA01

The initiatives taken on all levels facilitated the access and the acceptance of the force in the AOR. Its heavy equipment, weapons and armour were, however, not appreciated by all parties. In spite of this, its results on the ground compensated for late reconnaissance. Due to the close contacts between subunits, the population, and the fighting factions, the battalion learned about the conflict, developed its methods and routines, could act and report – it made a difference. Relations with the local population and even with the warring factions were built on respect and competence.

However, it seems as if separate worlds co-existed, or rather separate systems, each one with its boundary zone which they guarded against surprises: the Nordic battalion, BH Command (and the rest of UNPROFOR), the Swedish Joint HQ. It was difficult to communicate between them – the different number and kinds of reporting systems were not enough to overcome this, no matter if the report was sent to Sweden or to the BHC. One can say that these systems rested on separate local rationalities and each was, at least occasionally, in the other’s boundary zone. To build bridges between them required much effort and trust – issues that were in short supply in Bosnia. Whether this is unavoidable or not is up to others to judge but it had practical consequences:

“On one occasion the CO came and said the HQ staff lived in a damned fantasy world, that we busied ourselves with totally wrong things. But that was because he had been down and met those gangsters in Vareš during several days, and we hadn’t.” (COS June 1994, translation by first author)

We must introduce another term from systems theory in order to understand how BA01 operated: requisite variety (Davis and Olson, 1984). Any open system must have the capability to vary its behavior as the response to variations in its environment, especially if it is a control system – which from a theoretical perspective the battalion was. The intelligence (sub-) system as its warning system has to categorize and then communicate about events and changes. Any administrative element in an organization uses a limited number of recognized terms, especially if it is automated, and it may require much effort and time to adapt it to a different type of context (for example, a database for storing of reports). The best administration can respond fast to expected events, but cannot easily respond to the unexpected – as in the Bosnian environment – which can be very difficult to deal with. In a computerized control system, the computer applies (decision) rules to generate control responses for all expected situations. A human decision maker is, however, used to generate responses for the unexpected. And if we turn to intelligence, this is the reason why HUMINT is so important in unexpected situations. Humans can respond to the unexpected (Hedenskog, 2003). In his accounts from the mission, Henricsson (2013) underlines the crucial importance of eye-contact and to be close enough to read the body language in any situation, because the choice between “firm, fair, friendly” basically depends on non-verbal communication. With few exceptions, the BA01 presence was characterized by personal interaction which gave almost instant variety, either the option for interaction was tank fire, eyes that met over the barrel of a machine-gun, or a glass of slivo.

In other words, efficiency and rationality, as we understand the terms, especially when linked to technology, is neither enough to support intelligence collection – or rather “the design and production of input (data) for reports” – nor analysis even in war environments like Bosnia. Neither is it enough to say that, if we expand our definition and strategy of war to include social and cultural factors, this will be sufficient. Even if we did this, and were also able to address all the institutional issues that stand in the way of effective intelligence collection and assessment, this would not be enough either.

What would still be in the way is a kind of colonialism of mind (for example, that a conflict is ethnically and religiously driven instead of economy-based), which makes us believe that events and our understanding of them are seen the same way by our opponents.

To meet another person face-to-face, and use voice and images, add to the necessary communication variety but may imply large transaction or translation costs for the rest of the administration. As regards the technology part of the sociotechnical system, the use of a variety of technologies illustrates how pieces in a cluster or cloud of artefacts were combined in order to get rapid answers on upcoming questions or solve problems that threatened the survival of the force and sustain its ability to fulfil the mission. The art of combining technologies and solve problems was not only evident within intelligence as directed to the fighting factions, but also when it came to the use of vehicles and means of transportation and re-design depending on actual conditions. Terrain analysis sometimes had to be done with the most obscure technical vehicle detail in mind.

The concluding words from the former IO (February 2015) were that the team discovered that their work structure had to be situation oriented. Rules were worth less than experience. They learned their job the hard way but failed when they tried to transfer it to their successors in BA02, who were “programmed” only in the Swedish structure.

The Second Nordbat 2: BA02 established relations in the area

The original after mission interviews in 1995 were made with the battalion’s Commanding Officer (CO), its Chief of Staff (COS), the Liaison Officer (LO) and one Operations Analyst (OA). Some additional experiences from the third battalion have been included.

Mission Policy

The expectations within the second Nordbat 2 (BA02) were coloured by the first battalion’s ongoing struggle to live up to the mandate and the mission. Even if the war still was substantial, a lot of shells were fired in the area and from time to time they used their own weapons, the second battalion’s approach differed. Their motto was to establish presence of the battalion. “Actually it was like a three-stage rocket”, its COS said. Companies’ and their commanders’ combat attitude had to change.

The CO explained the changed policy in the after mission interview (March 1995). He meant that the BA01 had too many armoured vehicles and looked at the world only through glass prisms from under closed hatches. His battalion tried to open the hatches, see the population, and patrols were ordered to stop and chat with people. He used a Toyota – not an APC (as a matter of fact, also the CO in the first battalion used a Toyota when the circumstances allowed this). One of his examples was when representatives from the battalion visited the local radio station dressed in combat gear and carrying weapons – their appearance became a barrier in that context.

According to this battalion’s COS their “business policy” had three steps. Step one was to create preconditions for the humanitarian support of the population, by supporting UNHCR and build roads for example. Step two was to collect “humanitarian” and military information about the situation to the political decision makers. But the COS meant that the battalion did not have that in their mandate even if the policy-level had “some kind of intelligence function”. Step three was to be a reserve force to use when a cease-fire agreement was signed, to supervise it.

The LO stressed that Liaison was the function where continuity was most important: to be introduced and build relations require time.

Eventually, the battalion developed friendship with some Bosnian forces – maybe they became too close friends, the COS said. But this gave a lot of insight and, in addition – “after all we are their guests”.

Cooperation and Surveillance

Personnel from the battalion moved freely in the town, asking about peoples’ sentiments and thoughts, and immediately learned when men were forced (“recruited”) into the military.

- When being out in the woods searching for mushrooms together with civilian Bosnian acquaintances, one learns a lot about the undercurrents in a society, said the COS.

Another example was the way the political evolution was studied.

“We monitored the canton elections very close. We knew the guy privately who won the elections, his name was H. We also knew what the opponents and the Mayor thought about this election and its results, and the procedure. But the UNPROFOR was completely uninterested. They had their Civil Affairs organisation which handled this. [……]…from their strict point of view ours was a military mission.” (COS 1995, translation by first author)

The COS meant that the actual competence in the battalion surpassed the expectations on it. The unit was not used to its capacity. Behind this statement lies the fact that the Swedish units had no professional soldiers. Instead they consisted of former conscripts who brought their civilian education, professional and business experiences with them to the mission and could do more than soldiering.

Fixed Observation Posts (OPs) complemented by mobile OPs in the form of APCs whose positions changed from day to day were the main resources. The positions were inherited from the first battalion and linked to the supply roads and the traffic. Artillery fire was frequent. It varied from a few hundred to two thousand shells per day and was counted and reported. The insight that the Serbs were firing to scare the UN force rather than inflict casualties made the sentries on OPs keep their positions in spite of the firing and that grenades landed successively closer – from 200 meters down to only 50.

The artillery radar company manned by a Jordanian UN unit did not function satisfactorily due to limited skills and unsatisfactory maintenance, probably a consequence of the technical service agreements with the US.

Before a Bosnian offensive, the UN troops were forced out of the area. The reason for this expulsion was that probable reports about troop movements in the UN chain of command, for example that a Muslim brigade had been moved, meant that the Serbs learned about them.

British Special Forces (SAS[23]) operated in the area – seemingly under direct command from General Sir Michael Rose, the commanding general in BH Command (“his private army”, COS, 1994 interview):

“We told them ‘damned you have to put on a blue beret’ [….]….when they were stopped in a road checkpoint they said they belonged to the Nordbat…[….] then representatives from the Bosnian 2. Corps came and said – informally – ‘there will be a fatal accident with these guys if they do not begin to visibly wear a blue beret. Our men can bring them to the Serbs if they continue.’ And another day they came and told that an English team was observing us – which was a surprise for us. Rose used them for surveillance of his own UN force.” (ibid., translation by first author).

Later it became clear that this “friendly” surveillance was an effort to clarify the existence of corruption in the UN. Like a secret police, the COS said:

“They claimed all the time that the UN is like a sieve and I share this view. One has to search for an organisation that leaks more, a more criminal organisation than certain units. ..[…..] one understands their actions when they [the Bosnian forces] curtained the area and we were quarrelling at checkpoints..[.] but in retrospect I sympathize with them.” (ibid., translation by first author)

Assessment and Reporting

Military units cling to traditional patterns – can the military do anything else than administer Red Force and Blue Force? the LO asked. This officer had found reports about local forces very fragmented. Little systematic analysis was done – nobody in the staff was trained in intelligence. Not even the Intelligence Officer was adequately trained – he had never had this kind of job – but it was not possible to find someone who was.

Why were the OPs fired at? It was difficult but necessary to define an interpretive framework for this situation when there was neither a declared war nor open hostilities against the UN. He had experienced how the Sector HQ (UNPROFOR Sector NE in Tuzla, established during the mission period) had had a very vague view on the situation. He gave an example: The sector had ordered “Get closer to the confrontation line. Fight for freedom of movement.” He wondered whether they really meant “fight for”.

The OA officer confirmed the mixed feeling towards this HQ – it was put in place too late and should have had more competent staff. Thinking on his position and the battalion HQ, he appreciated that he had had the opportunity to work in an OP. There he had learnt about the environment, about what people could see, and how to distinguish between different explosions and weapons.

The COS explained that the combat intensity was estimated based on the main indicator, the number of detonations from artillery fire, even if it was difficult to report details about the fire. An OP cannot always judge outgoing-ingoing but calculates the direction and estimated distance to an explosion.

He believed that the use of artillery had various purposes. It was a political signal rather than aimed at maximum effect in a target; it was a way to keep the war going; and that a certain number of grenades had to be fired – but not necessarily causing damage. In other words, the factions were engaged in a kind of collaborative effort to “keep the kettle boiling”.

His conclusion was grounded in a growing friendship with a medical doctor in Tuzla, an orthopedic surgeon. If, the COS said, artillery fire had caused a lot of damage, then there would have been more soldiers wounded by shrapnel. Instead, the most frequent wounds were caused by mines.

Another assessment and reporting example concerns roads and traffic. Road traffic was monitored as a step 2 activity and the number of trucks was counted. If, suddenly, a lot more trucks than was normal headed north, the COS understood that something was under way. But they decided not to report troop movements, because the UN coding system was very simplistic and individual officers leaked UNPROFOR information to the Serbs. So, the battalion simply did not report specifically about positions and certain units due to considerations about the 2. Corps. The reports were not seen as necessary for superiors.

Depending on the tension, reports from companies were ordered twice or four times a day. The attitude from UNPROFOR seemed unfair. Normally “Sarajevo” (BHC – actually it resided in Kiseljak) was not interested at all, the COS said; if the factions destroyed, for example, the centre of Tuzla, it was a cold case compared to when the UN was involved and Serbs were wounded.

“…There were artillery shells over our soldiers all the time……..very close and they fired at us…..we reported but one never heard anything when our guys… but if we fired at them [the Serbs] they [BHC] were very eager to know exactly who it was, under what order, what mandate. But if the Serbs amused themselves by targeting us they were more cold-hearted.” (COS, 1994 interview, translation by first author)

The COS underlined that the mandate excluded espionage against the host nation, i.e. directed intelligence efforts, and that the UNMO teams did not work as professionals. They collected everything they noticed and produced nice artillery maps and similar devices, just as proof of concept, but “then it is certain like Amen in a church that this nice map was leaked” [to the other side in the war].

We include only one comment from the third battalion’s (BA03) Military Information Officer (MIO) who in April 1995 at the after mission seminar[24] confirmed the view that reports from the battalion were filtered before they were sent. Bosnia had accused the UN of espionage. It was important to establish trust for S2 during collection, to brief their own units and be visible among them. Intelligence analysis was done on a weekly basis. Only events that concerned the security of the battalion were reported.

Conclusions

These accounts indicate that the second battalion tried to act according to the changed environment, and that efforts were made to come closer to the local communities than its predecessor. The UNPROFOR organisation was still evolving, which hampered the overall understanding of the situation. Limited technical resources and competence constrained the battalion’s intelligence (collection, reporting and analysis), and new approaches were tested.

It is doubtful whether there was any continuity as regards intelligence from the first to the second battalion. Some accounts even indicate that BA02 “went native” – maybe it was used for purposes they were not aware of.

One can discern low trust toward the UN system – if there was any. In the same way as the first battalion practiced, reporting that could be harmful for the Bosnian army was held back or filtered.

Whether this was counterproductive for the mission or not is impossible to say, but it may have been advantageous for this force.

UNPROFOR HQ 1995 – closing the gaps

This section is based on the personal experiences of Col. Svensson from his service as the UNPROFOR/UNPF HQ Chief G2 in 1995, with some sentences being citations from his personal accounts.

The conflict and the UN intelligence system up to 1995

In March 1994 the UNPROFOR mandate had, in the same ways as happened before, been extended six months. In a report in September 1994, the Secretary General (SG) described the difficulties which were inherent in UNPROFOR’s nature “as a highly dispersed and lightly armed peace-keeping force that was not mandated, equipped, trained or deployed to be a combatant”. On 30 September 1994, the Security Council again extended UNPROFOR’s mandate till 31 March 1995, but during the fall fighting escalated. In November NATO aircraft were called in for air-strikes against antiaircraft missiles and to protect the UN forces[25].

In summary, in the beginning of 1995, the conflict in ex-Yugoslavia was in some sort of a stalemate. A lot of activities took place in the diplomatic field, but no solution was in sight. Hitherto, the intelligence system had demonstrated the UN-related characteristics.

Traditionally, intelligence is a term related to national security, covert methods, secrecy, deception and closed communities. This tradition contrasts and is contradicted by UN principles that are founded on transparency, impartiality and multilateral cooperation. One UN principle is that all information and its storage have to be public, open and transparent but may also lead to security problems in a mission mandate as UNPROFOR/UNPF. The principle may also restrain some national intelligence agencies from providing intelligence to UN.

The UN is forced to rely on different nationalities’ and organizations’ good will to share information. Sharing of intelligence between states is based on bilateral agreements, and the states have to stick to “the third party rule,” which means not to share information with the third party without permission from their counterpart. It was complicated for UNPROFOR/UNPF to get information from a nation. UN had to ask for intelligence through this nation’s delegation to UN in New York – which almost never happened.

Countries which have contingents in a UN operation usually have well developed intelligence resources outside the UN framework. Part of a nation’s intelligence-based information is not available to other participants, because the member states sometimes will support their own interests that may be contrary to the mandate. In a UN mission, it is necessary that there is a free flow of information relevant to the mission for all participants. Member states and organisations may hesitate, because intelligence submitted to the UN will be accessible to others, and the contribution will be sanitized in order not to reveal their capabilities and sources. The only restriction should be measures taken to protect the sources. It is, however, also important that the UN does not leak information to the warring factions. As we have seen, leakage existed and probably hampered the peace process – reports from the field were held back.

Lastly, UN intelligence capacity has often been based on those individuals in the system that have become regional experts on the theatre of operation through their own “networking” and “data mining”. They build up contacts across agencies and organizations. The disadvantage is that, when the individual expert leaves the area, the knowledge is lost.

The common opinion in the beginning of 1995 was that UNPROFOR had bad intelligence and did not know what happened, but Svensson rejects this view:

“That is not true. We had very good control of the situation but the political level did not listen to UN analyses and advice. I got a question every week about the situation in the enclaves Srebrenica, Zepa and Gorazde and my answer every time were that the enclaves could be defeated whenever the Bosnian-Serb Army wanted to do so, but the political circumstances had to occur. The UN/NATO airstrikes was a moment that triggered the atrocities. G2 and UNPF leadership advised against to start air strikes but the UN and the “big members” did not listen.” (Svensson, in De Jong et al., 2003; citation for this paper, 2015)

Then, what was achieved in 1995?

The situation in the UNPROFOR HQ

The Intelligence Branch (G2) in UNPROFOR/UNPF in Zagreb worked on building a professional intelligence organization. The work had to be organized according to the considerable dynamics of the UN operation.

G2 was manned with officers from 13 countries, speaking 11 different languages. Among about 30 officers posted to G2, only half of them were operational because of poor English and insufficient knowledge of the conflict. Moreover, some member states sent officers just in order to fulfil their commitment to UN rather than send experienced and trained intelligence officers.

The work in G2 was complicated because the mission was very “NATO”: G2 was, to a large extent, manned by officers from NATO-countries, and those officers had access to information superior to others. In a conflict infected by different conceptions of the solution and of how to attain it, it is advantageous to try to be impartial, but difficult.

As a Swedish officer, coming from a non-aligned country, Svensson had no official access to intelligence coming from NATO. A lot of informal structures are intertwined with formal structures. Unofficial networks are often used to pass intelligence. Also, some staff had a tendency to act in their own interests to position themselves internally and sometimes obstructed sharing of intelligence:

“My striving to be impartial caused some clashes with my peers because of the pressure from their respective home country to impact the assessments.

But by building confidence and credibility I succeeded in getting information that was necessary for me and my staff to understand the situation in the conflict. However, my cooperation with NATO intelligence officers was excellent, though on an informal level………………… Sometimes intelligence is provided face to face and with the caveat that only a few members mentioned by name will get the information. As an example I got intelligence from some NATO-countries that was marked “Releasable to Colonel Svensson”. I had to handle such information very carefully. “

The intelligence officers would often take heed of the prevailing political and military views in their country of origin, which sometime led to politicized intelligence.

G2 received reports from different levels in the organisation. Daily information summaries were sent from commands, sectors and battalions. The reports from the battalions were detailed and their assessments reflected fragments of the overall conflict. The G2 analysts were literally swamped with these details. The report system confused the intelligence officers on the mission level and also caused the staff to work with too many details.

In addition, mutual distrust reigned: Because of the involvement of troop contributing nations and possible political pressure on the commanders and staff members, the higher echelons did not trust the assessments from subordinate commands and sectors, and these did not trust their superiors. Svensson remembers:

“When visiting sectors and commands in UNPROFOR/UNPF I experienced that the perspective of the conflict differed. My credibility was questioned when we had briefings that reflected our perspective on the conflict.”

G2 could get NATO air recce reports but photos were of limited use because of the type of warfare by infantry in rough terrain, urban areas and with soldiers intermixed with the civilian society. Even if weapons such as individual cannons or tanks occasionally could be seen, analysis was hampered because G2 could not relate such objects to any military force structure. On one of his reconnaissance trips Svensson saw how in the village of Sunja, close to the confrontation line and SE of Zagreb, a street was blocked by a plank (Figure 8).

Figure 8. A view of a blocked street in the village of Sunja at the confrontation line, Spring 1995. Photo by Jan-Inge Svensson.